It's the same old question again which noted jurist Fali S Nariman argues is not so much legal or constitutional as is sociological.

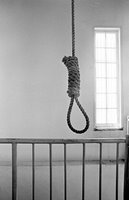

It's the same old question again which noted jurist Fali S Nariman argues is not so much legal or constitutional as is sociological. The hangman's noose is again in the news-thanks to the front-page of The Indian Express (October 17). But it has long been on the conscience of legislators, of judges, and of the thinking public, and also (it would appear) on the conscience of President Kalam: his humane stand has a stirred up a controversy. It needs stirring up. The truth is that the death penalty is not so much a legal or a constitutional issue, as a sociological one. It evokes divergent responses in different people-and judges, being human, are no exception: nor are Presidents. There are the abolitionists, and the anti-abolitionists.

In India there has always been a cleavage of opinion. For some (as with our President), it is a matter of conscience. I remember my senior, (Sir Jamshedji Kanga) telling us in the 1950s about a senior District Judge, Mr. Khareghat, who was due to be elevated to the Bombay High Court. In those days the capital sentence could only be imposed by a High Court Judge. Khareghat declined the honour on the ground that he would never be a party to the death sentence: he would rather not be a High Court Judge. (That is why we remember the name of that District Judge!)

The abolitionists have a strong lobby. Recent events in various countries (especially in the developing world) have driven many to the conclusion that murder will never cease to be an instrument of politics until the execution even of proved murderers is regarded as immoral and wrong. In the world of today there are fewer and fewer men condemned to death for murder, and more and more executed for political views.

As long as death remains a permissible instrument of Government, those in power will always justify its use. Besides, (and this is a particularly pertinent point) the hangman's noose ends the search for truth-what if the judge is wrong? The question plagues our consciences. Judgments of Courts can always be recalled and reviewed; execution of sentences of death, never.

I recall what Niall Mardermott, distinguished Secretary General of the International Commission of Jurists, said whilst conveying to the then President of India, ICJ's plea for mercy for Kehar Singh (one of Mrs. Gandhi's assassins) "in the country of my birth (the Republic of Ireland) there is a saying that the grass never grows under the gallows". But President Venkatraman had already made up his mind-and Kehar Singh was hanged.

The main plank of the anti-abolitionists is that the death sentence has a deterrent effect-not by the fear of death, but exciting in the community a deep feeling of abhorrence for the crime of murder. I remember in 1973 when Jagmohan Singh's case was being argued, (where the constitutionality of the death penalty was first upheld) Chief Justice Sikri said, in the course of arguments, that he was certain that if the death penalty were abolished, entire villages in the Punjab would be wiped out in a wave of reprisals! He had been the Advocate-General of that State for many years.

Other Justices from this State and other border States have expressed similar views. How can a deep feeling of abhorrence of the death penalty be sustained, (say the anti-abolitionists), when known and hardened criminals sentenced to imprisonment for life, are set free through paroles and remissions after only a few years of incarceration? They have a point.

What then of the future? In the Oliver Wendell Holmes Lectures delivered in September 1981, Justice Brennan said: "I believe that a majority of the Supreme Court will one day accept that when the State punishes with death, it denies the humanity and dignity of the victim... That will be a great day for our country and our Court". He was speaking about the United States and its Supreme Court of which he was a distinguished member.

There are many in this country who would like to see the Supreme Court of India utter similar sentiments. Perhaps, hopefully, one day, it will-but I venture to predict it will only be when the system of criminal justice effectively ensures that persons who would have hanged but for the constitutional outlawing of capital punishment (like persons guilty of horrendous murders) would not return to society until reformed. Till then, the great question will continue to haunt us all (as it haunts our President): is it really necessary to hang people in order to convince people that killing people is wrong?

No comments:

Post a Comment